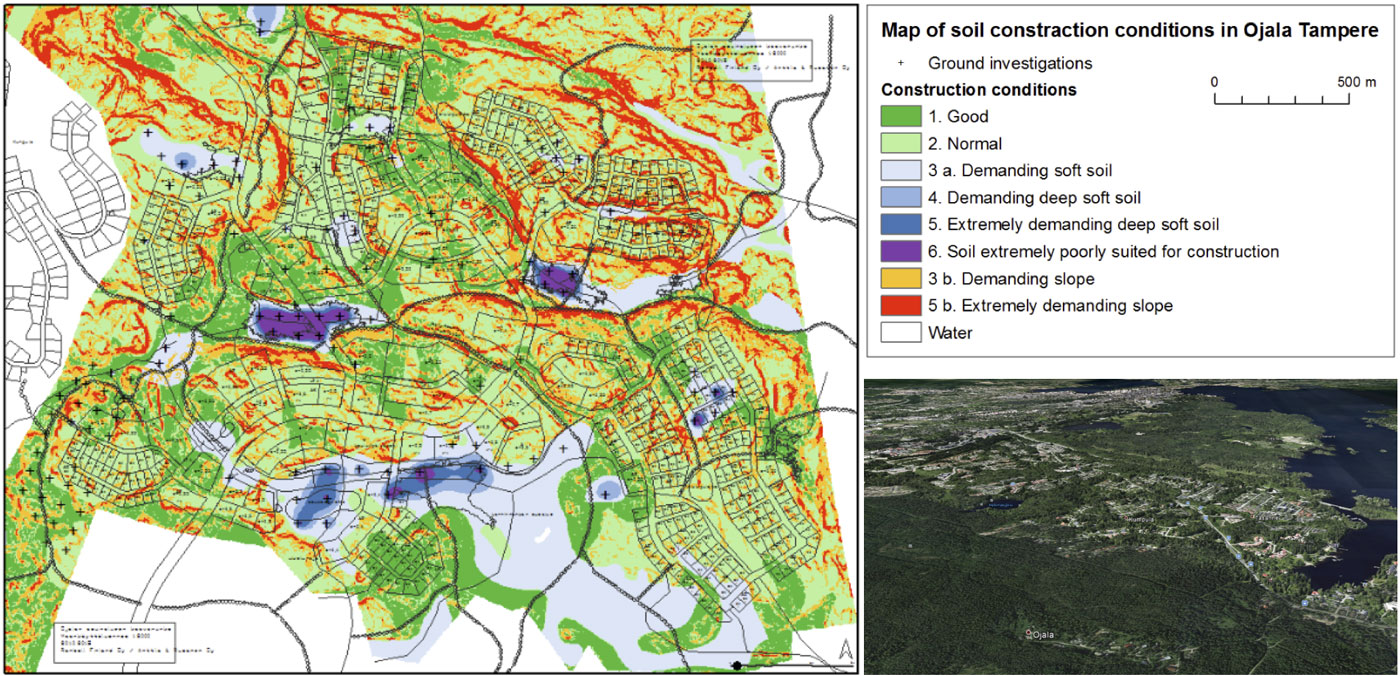

A Finnish experimentation project developed a framework for classifying ground conditions for building and infrastructure construction. It will help anticipate the future cost of foundation laying during the early stages of city planning.

The ground

conditions of an area can have a substantial effect on the costs and the

environmental impacts of constructing buildings and infrastructure. At early

stage, urban designers don’t typically have enough data to make smart decisions

about zoning in that respect as obtaining that data is time-consuming and hence

also costly.

Consequently, an experimentation project called MAKU-digi: Making the costs of land use visible devised a method for automating the analysis of ground conditions. I had the pleasure of interviewing Juha Liukas, Lead Advisor at Sitowise, and Hilkka Kallio, Geologist at Geological Survey of Finland (GTK), about the project.

Brewing the Idea

“While we

were developing the Citycad software back in the 1990s, we had this idea of

combing a ground conditions map with a town plan for analyzing constructability,”

says Liukas. “One of our clients was the city of Espoo, which had just mapped

out the city’s ground conditions.”

However, turning

this idea into a method and a practical tool did not materialize until much

later. In early 2017, Sitowise, Geological Survey of Finland, and six other

organizations started an experiment as part of the national KIRA-digi

digitalization program. The project was called MAKU-digi.

Espoo had

meticulously kept its ground conditions data up to date and was invited to take

part in the project. Other large cities—Helsinki, Vantaa, and Tampere— soon followed

suite, together with the Finnish Transport Agency. They provided the project with

five pilot case studies.

The Sources of Ground

Conditions Data

As ground

conditions data is not readily available in every part of the country, cities use

local geotechnical investigations to augment data from national sources.

“At GTK, we

carried out a 35-year mapping project of superficial deposits, which created

geographic data as polygons,” says Kallio. “This gives an overview of soil

across the country, 1-meter deep. I think, in the beginning, soil mapping was

mainly meant to serve agriculture and forest planning. Today our soil maps are

widely used by land use planners”

Ground-penetrating

radars, satellite imagery, and drone surveys offer additional data that

geological experts can use to estimate ground conditions. However, Kallio

emphasizes that geophysics does not offer alone accurate enough information for

construction purposes. She would rather rely on geotechnical investigations as

primary data.

Automating Geotechnical

Analysis

A two-by-two

kilometer area can involve up to 10,000 individual geotechnical investigations.

Analyzing that amount of data manually is impractical. Thus during the project,

GTK devised and tested a system that automatically identifies certain beds and

strata in the ground.

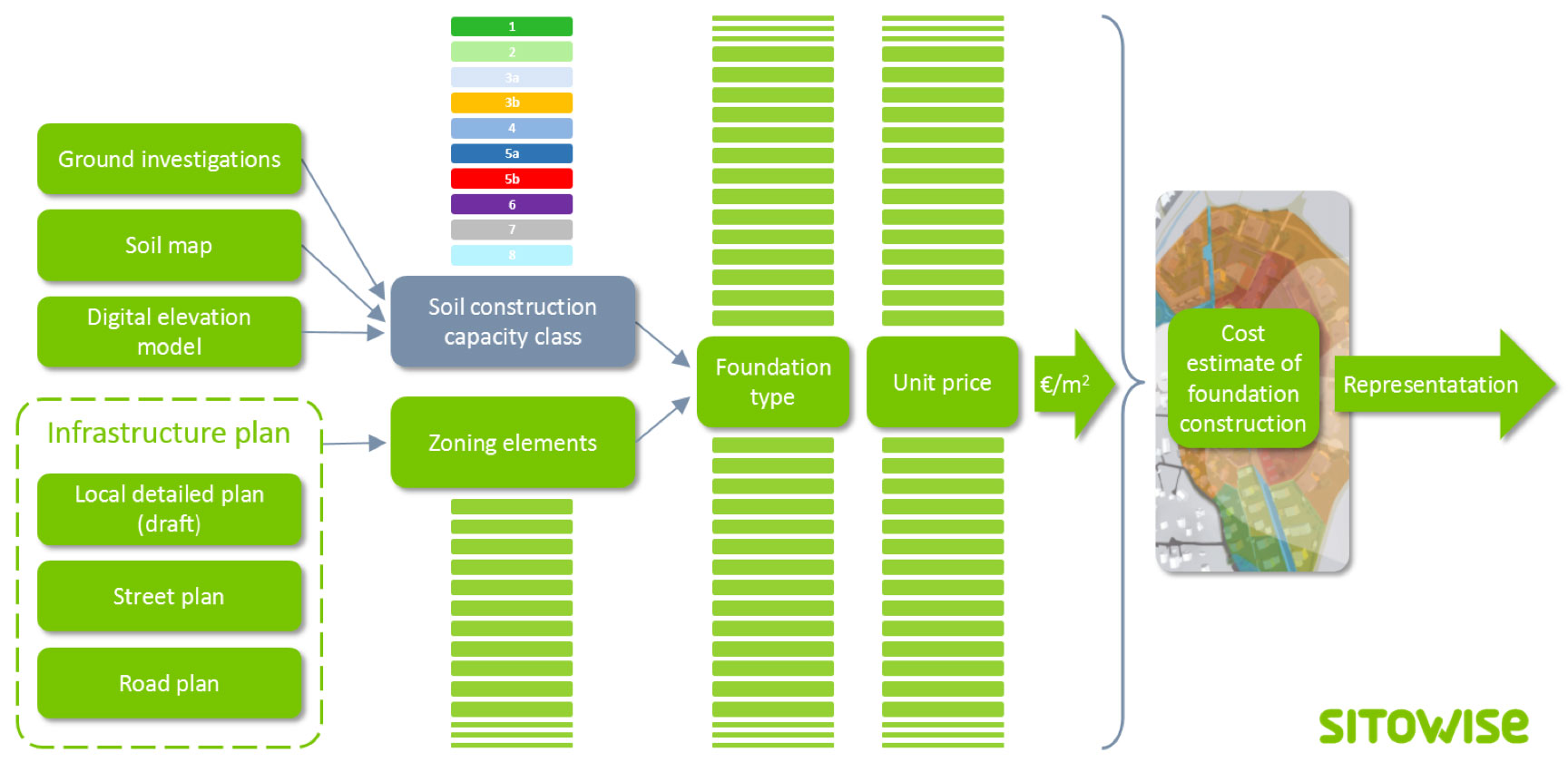

The other

main output of MAKU-digi was a system for using geotechnical investigations,

soil maps, and digital elevation models to classify any geographical location

on a standardized scale. The “soil construction capacity class” of the

location, combined with the location’s zoning elements, determines the

foundation type. It, in turn, has a unit price that when multiplied with the

building area gives an estimate of the foundation costs. The results can be

presented visually on a map.

“In

MAKU-digi, we dealt with the relative rather than absolute costs of foundation

construction. There are other projects, like the national IHKU Alliance, that

will provide a cost management system for infrastructure construction,” Liukas

points out. “I envision a future where you can upload a draft detail plan to an

online service and see the updated foundation costs at once, even as you make

changes to the design.”

Harmonizing Urban Design

Data

“The

Ministry of the Environment saw our results and came to the conclusion that our

harmonized classification model could become a JHS recommendation,” says

Kallio. The so-called JHS recommendations provide national information

management guidelines for both governmental and municipal administrations.

Another

project called Municipality Pilot is formulating a process and information

model for digital detail planning. It has tested combining a detail planning

model with the MAKU-digi analysis in three municipalities.

“I don’t

know of any examples from other countries where a ground condition method and classification

is standardized at the national level. So in that sense, we are doing

pioneering work here in Finland,” Kallio concludes.